10 Reasons Why Hebrew Is Easier Than You Think

Written byMarta Krzeminska

Written byMarta Krzeminska- Read time9 mins

- Comments4

Hebrew is easy.

Wait, what?

That language with a curious-looking square alphabet written right to left? Come on, it can’t be easy!

Alright, Hebrew definitely has some novel elements — every language does. But, I’m here to tell you that despite these features, it’s definitely not such a language Behemoth as some may suggest.

The knee-jerk response we often have towards languages which use different alphabets, and come from different language families is … fear. This ‘linguistic anxiety’ causes us to avoid learning them, or postpone starting until time indefinite.

Starting with a belief that Hebrew is hard, can also make learning process slower due to the confirmation bias it triggers.

Convinced that a language is complicated, you will only pay attention to cues which confirm this hypothesis.

If the only thing you remember after every study session is a long list of obstacles, you’ll definitely feel far from being encouraged.

The learning will stop.

The progress will stall.

You will fail.

And by failing you will ultimately confirm what you believed to be the case from the start — that Hebrew is hard.

I’m here today to prove to you that this underlying assumption is wrong and that Hebrew is easier than you think.

What makes Hebrew hard?

In order to approach this question, we need to first identify the characteristics that learners may find hard in Modern Hebrew.

Then we can dismantle them one by one.

Brace yourselves Hebrew skeptics!

Here. We. Go.

Hebrew Alphabet

An alphabet different than the Latin is often seen as a barrier to a language.

How can you write down new words if you don’t know the letters?

1.There aren’t many characters to learn in Hebrew

True, the Hebrew alphabet is different from Latin.

But, its difficulty pales in comparison with other writing systems — the thousands of characters of Chinese, the four incarnations of almost each letter in the Arabic abjad, the mysterious squiggles of Georgian.

There are only 22 letters for you to learn.

Only five of them have a final form — that is, they look different when used at the end of the word than when they appear at the beginning or in the middle.

That makes only 27 new symbols to learn to recognise!

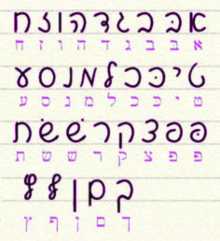

2. Cursive and print aren’t that different

In Hebrew, there is no stark difference between the cursive and the printed script.

Unlike in Russian, where the two are poles apart, Modern Hebrew cursive in most cases resembles its printed parent.

To the same extent at least the printed Latin characters mirror the scribbles we put in our language notebooks!

Point to consider: Nothing stops you from learning to speak first, before mastering the art of writing.

You can opt for jotting down words and phrases using Latin letters, while you continue slowly working on the Hebrew script on the side.

Hebrew Vowels

3. Hebrew is logical

You’ve probably heard that Hebrew is written ‘wtht th vwls’ (“without the vowels”), and might ask in fear:

“So how do I know how to read things aloud?!”

Learning Hebrew is like training yourself in pattern recognition.

Hebrew is a Semitic language, and in languages from this family words are constructed around three or four -letter roots.

A root is a combination of letters that contains the core meaning of a word.

The meaning can be modified by adding specific combinations of vowels, prefixes, and suffixes.

As you learn Hebrew words, you learn to recognise different word patterns and after you’ve acquired one pattern you can apply it to new roots. Isn’t it cool?

Learning Hebrew grammar is like reading through a recipe book of words’ creation!

4. You can skip the vowels

You might have seen texts in Hebrew that look like a top of a birthday cake — covered with sprinkles.

These ‘dots and dashes’ are the nikkud — vowel symbols.

They are used in texts aimed at children or beginners to help students read before they learn to recognise patterns and cope without the vowels.

If you learn Biblical Hebrew, you will have to learn vocalisation rules — rules governing how to add the vowels to a text. And, those rules are pretty convoluted.

However, as a learner of Modern Hebrew you can simply skip through that.

As long as you know how the vowels look, you are sorted for reading.

Hebrew Grammar

5. Hebrew has only one article

People tend to list Spanish among languages easiest to learn.

But just look at the number of articles Spanish has: definite and indefinite, singular and plural, masculine and feminine! This seems a little excessive.

What’s the situation in Hebrew?

Hebrew has just one definite article marker.

And, it stays the same regardless of the gender or the number of objects we’re defining.

What it means in practice is there is no need to learn endless rules and exceptions of using the article.

If you speak English — at least to the extent that you’re able to understand this article — you have already cracked the concept of the definite article, and the Hebrew one will not cause you any headaches.

6. Hebrew has just one case

Move aside Russian and German — your case systems are slightly overboard in comparison to Hebrew.

Hebrew only has the accusative case – a special marking of a direct object in a sentence.

In many other languages using the cases involves multiple changes to the forms of the nouns. You’d be thrilled to learn in Hebrew the accusative case requires adding only one small particle, ‘et’ () before the noun.

Let’s see an example.

In English you say:

“I received the excellent advice from Marta.”

In German, to apply the accusative case you’d have to change the words: the, excellent, and advice.

In Hebrew you’d only to need to add ‘et’.

I received… ‘et’ ()… the excellent advice from Marta.

Now, isn’t that excellent?

7. A ‘semi-Semitic’ language

I mentioned before that the fact that a language comes from a different language family can be off putting for some learners.

It can make you fear peculiar features and concepts that are hard to wrap your head around.

While Biblical Hebrew is a Semitic language, the status of Modern Hebrew is debated (cf. Ghil’ad Zuckermann). The language has adopted many syntactic features of Germanic and Slavic languages, and lost a few characteristics typical of Semitic languages.

So, worry not!

Modern Hebrew follows the familiar subject – verb – object (SVO) word order rather than VSO (seen in Arabic), it doesn’t use the dual number and, as mentioned before, has only one case.

In other words, Modern Hebrew shares the logic of Semitic languages with its approach to word creation, but has lost a lot of their complicacy.

8. Rare irregularities

There are many languages in which present tense conjugation of simple verbs is the hardest.

To make things harder there often exist different conjugation patterns — each verb belongs to its own family or group which we have to remember in order to be able to use it.

Even with that attempt at organisation, the most commonly used verbs undergo the strangest modifications and are almost always exceptions.

A way to ‘encourage’ a beginner learner :/

In Modern Hebrew, to learn the present tense conjugation you only have to learn a few verb endings, which remain (fairly) regular across different verb types.

The default is the masculine, there are endings specific to a feminine singular form, to a feminine plural, and to a masculine plural. Whether the plural is ‘us’, ‘you’, or ‘them’ doesn’t matter.

The only thing that concerns us in Modern Hebrew present tense is the number and the gender.

Bonus: Think about the verb ‘to be’ in English. How similar is the word ‘be’ similar to ‘was’, ‘is’ or ‘am’?

Hebrew decided to make do without this complicacy, and simply not use the verb ‘to be’ in the present tense.

Clever choice. Why bother!

Hebrew Words

9. Hebrew loans a lot of words from other languages

Modern Hebrew has a long history spanning across countries.

Each of the periods of its development and locations in which it was used influenced its vocabulary.

The first and basic layer is formed from the words of Biblical Hebrew — many of which were shared among ancient Canaanite languages.

On top of that we have the Aramaic-based layer of Rabbinical and Medieval Hebrew.

The most important lexical influence on the language, however, happened during the Hebrew enlightenment. From around the 17th century when Hebrew was starting to be used again for the purpose of everyday communication, people were forced to create or borrow new words for concepts and things that didn’t exist in ancient times.

Reconstructed predominantly by speakers of Slavic and Germanic languages, Modern Hebrew uses a lot of words from common European languages.

Current influences of English and Arabic (including numerals) make it even easier to understand the language of modern Hebrew speakers.

Add to that a large number of immigrants from across the globe, each bringing in their own morsel of lexical novelty, and you have a vocabulary with many words you already know.

Hebrew Sounds

10. Nobody cares about accent

Israel is a melting pot of cultures (and adult learners).

Because new immigrants learn the language to be able to function in a new country, their aim is primarily to be able to communicate efficiently rather than impress others with their native-like skill.

The abundance of learners striving to reach fluency quickly results in an abundance of people on various language levels, and with accents from all around the world.

And the best part about it? They are all Israelis – citizens of the country – and holders of an Israeli passport.

What that means for you is that regardless of your accent people are likely to take you for an Israeli.

In addition, it means you will be easily understood.

Speakers are simply used to hearing Hebrew with a foreign accent, whether Ethiopian, German, or Peruvian.

So there’s nothing to fear as it comes to Modern Hebrew.

It’s time to embrace it.

This post was written by Marta Krzeminska.

Grab the link to this article

Grab the link to this article