How To Learn A Language That Has Really 'Hard' Grammar Easily

Written byHubert Nagel

Written byHubert Nagel- Read time8 mins

- Comments21

Happy Spring time, all

It’s been about 8 weeks now since I moved to Russia and started immersing myself in the Russian language.

Despite all the bad news coming out about the whole Russia/Ukraine thing, everything’s fine.

I was actually supposed to go to the Ukraine for my visa renewal this week but obviously that’s not going to happen now.

I’m now in Dubai again with my Russian host family for their holiday and after this I’ll probably have to spend some time in Estonia or Latvia for the visa renewal (Russia’s quite strict on visas so it’s a giant hassle!).

Time outside Russia is not ideal for me at all of course because I really don’t want any setbacks on my Russian progress, and being in another country is unfortunately time wasted in my opinion. I’m a little concerned that the current political climate might place delays on me getting my next visa so fingers crossed.

I have some unique language projects planned this year – some of which will work out a lot better if I’m conversationally fluent in Russian so the pressure is on to improve.

The good thing is I’ve got plenty of italki credits so it’ll give me a chance to use them all up with Skype lessons while I’m waiting.

Jump in and start to speak without getting bogged down in grammar study

When I first arrived in Russia I couldn’t really communicate in Russian at all.

As I wrote in my last post, I’ve been confronted by the need to speak Russian every single day since I arrived here. Even though I could barely communicate when I first got here, I was forced to learn as quickly as possible as pretty much nobody around me speaks any English.

I’ve started making some really special friendships with people entirely through Russian which has also been a great motivator to pick up the pace.

Now… Russian’s one of these languages that has a reputation for having painfully tough grammar.

Ask any experienced learner of the language why people think it’s hard and you’ll no doubt hear about things like verbs of motion, aspects and cases. These things would indeed be very challenging to memorize if you were taking the traditional ‘study grammar first’ approach.

I however do not and my experience and research have proven time and time again that it’s a mistake to start out like this.

As I wrote a while back in my popular and controversial post called ‘You Don’t Need To Study Grammar To Learn To Speak A Foreign Language’, this is absolutely the worst way to tackle any living language.

It’s unnatural, robotic and a real motivation killer for most people.

The problem with most language instruction is the idea that in order to become a fluent speaker of a language, one has to memorise all the rules and exceptions of its grammar first.

We learn languages backwards.

Speaking and using the language takes a back seat until you feel ‘ready’ (which for a lot of people never ends up happening).

It’s then no surprise that many of us studied grammar for years and still can’t speak the language properly or at all.

Learning a language by studying grammar first is like trying to learn how to ride a bike by analysing the mechanics of the cogs, pedals and chain instead of just hopping on the bike and falling off dozens of times until you can ride.

Eventually you’re going to have to fall off the bike anyway so you might as well start early and fail often because it’s the only way you’re going to improve as a speaker.

Being a social risk-taker then is key.

Listen, repeat and use whole phrases and expressions even if you have no clue how they work grammatically.

Use them hundreds – even thousands – of times until they become natural to you.

Take a simple sentence in Russian for example: Ты читaла эту книгу? Did you read this book?

In this tiny sentence there are loads of different grammar points that you could spend weeks or even months trying to learn through traditional study and memorization.

Just for this sentence alone, you’d be studying personal pronouns, verb tenses, gender, demonstratives, number, and cases as well as the vocabulary.

It’s a small but heavily loaded sentence and for most people the grammar study would be an instant motivation killer.

But suppose you just acquire and practise the whole sentence as it is, using it over and over and over again until it becomes habit and sticks.

The key word here is HABIT.

Make that sentence a HABIT that rolls off your tongue automatically.

You might think that by doing so you’ve only learned one sentence and a few words.

You’d be wrong.

By turning that one sentence into an acquired HABIT, you’ve learned an infinite number of sentences of the same structure and as your vocabulary grows you’ll start to naturally and automatically produce new sentences using the same structure without ever thinking about it.

Read what I wrote here and here if you haven’t already where I explained how the Lexical Approach works in more detail.

Rely on natural dialogues

It’s crucial to have good, natural dialogue material.

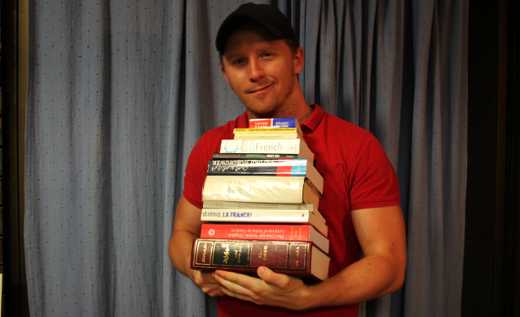

I’m finding the Assimil book series extremely useful but any good book with quality audio will work.

Another great resource that I’ve recently had the chance to try out is Glossika Spaced Repetition Training. I can only vouch for the Russian version at this stage but I’m truly impressed by what I’ve seen and it’s an excellent resource that I’ve found very useful over the last few weeks.

I’ll share more about my thoughts on this product soon.

Just make sure the sentences you use are spoken at natural speed and don’t use archaic, outdated expressions or overt politeness that you wouldn’t often hear in the real world.

Listen to dialogues in the same way you’d put your favourite song on repeat (again, the Glossika audio files are great for this). Go over it constantly, speak it and find every opportunity to use it.

Even if you only know one conjugated form of a verb or one noun form, use it as often as possible even if you know you’re using it incorrectly.

Some people will crucify me for saying this but…

Intentionally use wrong forms of nouns and verbs.

Deliberately making mistakes is better than not speaking at all.

When we don’t know how to say something correctly, a lot of the time our first instinct is to shy away from using it altogether until we’ve ‘studied it enough’.

My advice is to not be afraid to use the wrong forms of words or to say things incorrectly from the get-go.

If a learner of English said to me, “I to go the shop at tomorrow”, it would make perfect sense to me as a native speaker. Even though it’s grammatically very wrong I understand it and I can then correct the person.

I’ve been doing the same with Russian since I arrived.

There are a lot of Russian verbs for example at the moment that I only know one form of. Saying sentences like, “I to eat now” or “I to call you tomorrow” are grammatically incorrect but speaking like this is far better than shying away from speaking at all and it also means that I’m constantly learning from the corrections of my native speaker friends.

You’ll be amazed at how quickly you improve by not being afraid to make mistakes openly like this.

The feedback I get from native speakers when I do this helps me far more than trying to memorize lists and tables in a book ever would.

You’re also giving yourself a chance to get used to producing the language early on. If you wait until you’re ready to speak (which could take forever), you’re missing out on all that time to get used to producing the sounds of the language.

There’s really no difference between a language with ‘easy’ grammar and a language with ‘hard’ grammar

The reason why I titled this post How To Learn A Language That Has Really ‘Hard’ Grammar Easily is because by taking this approach, the difficulty level of a language’s grammar becomes irrelevant to you.

I’m learning Russian the same way I learned Korean for example which has a much simpler grammar in comparison.

Get to work on acquiring whole lexical chunks, listen to and repeat them constantly, and of course find every opportunity to use them.

Turn real language that you read and listen to into habit and save the grammar study for later on.

This was written by Hubert Nagel.

Grab the link to this article

Grab the link to this article