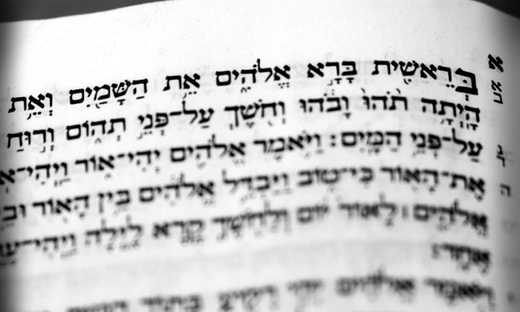

How To Learn The Hebrew Alphabet (+ Cursive) Quickly

Written byMarta Krzeminska

Written byMarta Krzeminska- Read time11 mins

- Comments1

A square script is scary.

It’s probably your first thought when you consider learning Hebrew.

The Hebrew alphabet looks intimidating when you first start a Hebrew course, but many have learned if before and proved it’s possible to master.

This post will provide a breakdown of the Hebrew alphabet.

But don’t worry!

It’s not a boring list of letters. We’ll take a trip through curious cursive and even some memorisation methods.

Learn the Hebrew script and get equipped to dive deeper into this wonderful language.

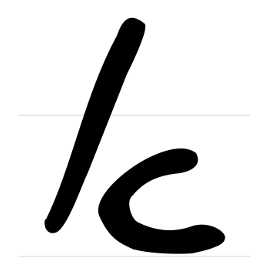

Aleph

Aleph is not just a short story by Jorge Luis Borges and a book by Paolo Coelho.

It’s the first letter of the alpha-bet, which make the character’s name pretty easy to memorise!

For the math-inclined among you, you might already know aleph from set theory, where it represents a specific set of numbers.

So clearly alephs are all around us.

But how do they look like? Let’s see:

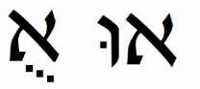

In print, the square script, aleph looks like a wobbly X — a little insecure perhaps?

But who wouldn’t be insecure if they were to open the alphabet.

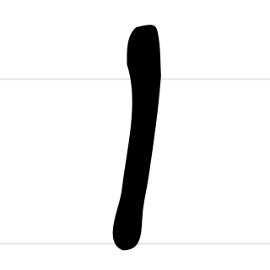

In cursive it ended up resembling the combination of letters l + c.

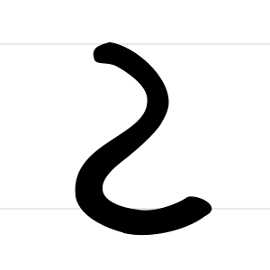

Bet

Bet () is, as you’ve gathered, the second part of the word alpha-bet which makes it the alphabet’s second letter.

Because it can also be pronounced “v”, it is also called vet.

Yup, like short for a veterinarian.

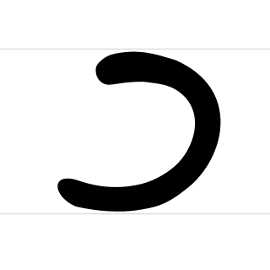

Conveniently, bet doesn’t look very different in print and cursive.

What’s your best bet to learn bet? Think of Betty Boop’s bottom!

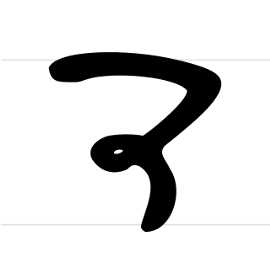

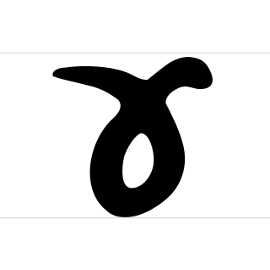

Gimmel

Funny one here – the print shape always made me think of a giraffe. Once you see the resemblance once you can’t unsee it.

It also seems like I was not the only one to match gimmels with giraffes.

In Hebrew the word for giraffe is exactly the same as in English — just said with an Israeli accent.

So by linking gimmel with a giraffe you won’t be creating a confusing connotation.

The cursive gimmel is a little different — it looks like a hook.

Think of catching that giraffe like a fish on a hook.

Dalet

The printed dalet looks like a part of a door frame:

Incidentally the word for door in Hebrew is delet, , quite similar to dalet, isn’t it?

The cursive dalt is a little funky — spiralled like a bit of pasta.

He

This one always made me laugh.

The name of the letter is often pronounced as hey which helps generate a cheerful connotation.

And you’ll need to be cheerful here because he is also the Hebrew definite article, and using it can be tricky.

Let’s not trouble our heads with this for now though and enjoy the grammatical obliviousness while it lasts.

Here is how we write He (): printed looks similar to the cursive version, the latter being a little more curved.

Vav

Another enthusiastic letter here.

Why?

Some pronounce its name as wow.

And it helps that it is actually shaped like an exclamation mark! Just without the dot.

Extra tidbit of information here: vav is also a full Hebrew word, and an important one at that.

It means and.

You will often see it preceding a he to mean and the. Hey wow! Isn’t that cool?

Zayin

Zayin makez a “z” zound. Eazy!

How does it look like?

In print it looks like a vav with a little dash on top.

If you add a similar one at the bottom it will actually resemble a “z”, which should make it easier to memorise.

In cursive it looks like a reversed gimmel.

The word zayin also means penis.

So as you’re learning to write it, don’t be surprised if people giggle when you ask them about the shape of their zayins.

Chet

Tricky times ahead friends!

Chet looks very similar to he, but without the gap between the two strokes.

If you think of this letter as a gate, it’s a much stronger one than the insecure, light-standing He:

The image of strength matches its pronunciation.

Chet is one of the harsh sounding Hebrew letters originating in the back of the throat. Harsh chet.

Tet

Like a small “t” without the dash, Tet () is one of the two ways to write a “t” sound in Hebrew.

Just like chet it looks almost exactly the same in cursive as in print.

To memorise it think of a thick nose. Tit for tat. Tet for nose.

Yod

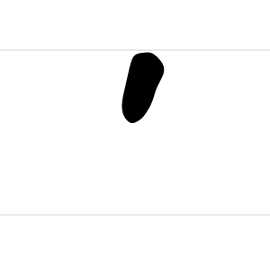

Where are you yod?

You’re so tiny we can barely see you!

Yod is the tiniest letter of the Hebrew alphabet.

Be careful not to confuse it with an apostrophe, a single quotation mark, or …a lost crumb from a burned toast!

If you place two yods next to a letter he, you’ll actually write “hi”in Hebrew:

!

And by the same token, guess what you’ll be writing if you add a double yod next to letter bet? Bye! A commonly used parting phrase in Israel.

!

Kaph

Welcome to your first, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde of Hebrew letters — a letter with two sides to it.

In most circumstances — at the beginning and in the middle of words — it looks like reversed a “c”:

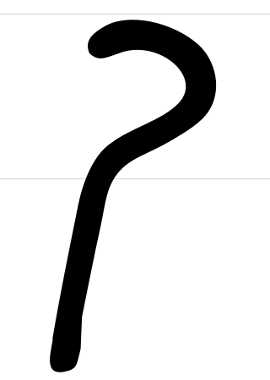

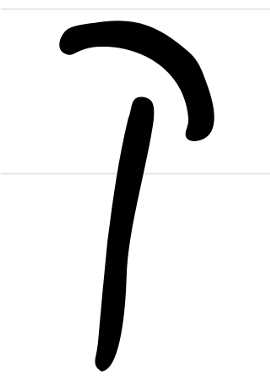

At the end of the words it looks like a cane.

In print it’s a type of cane your grandpa would use and in cursive more like a shepherds crook. Cane, crook, kaph:

Noah holds a letter kaph.

Kaph can pronounced in two different ways.

In the beginning and in the middle of the words either as “k” like in the English word character or as a harsh “h” like in the word Hasidic.

This is also the same pronunciation as of the letter chet.

At the end of the words it can only be pronounced as “h” – never as “k”.

Lamed

There is no other way of looking at it — lamed looks like lightning:

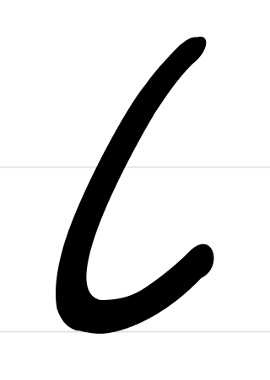

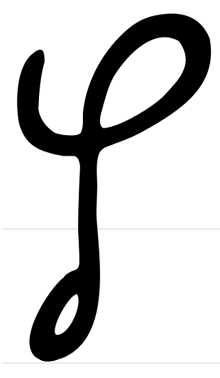

In cursive, lamed is one of the more fun letters to write.

It has a little loop at the bottom, and when you sdd two legs to it and it looks like a f-L-amingo. Or even a f-lamed-ingo.

Mem

I was tempted to make a meme about it.

Printed mem can resemble a minion pointing an arm up.

Mem is a second letter with a split personality disorder — it appears in two forms.

In its final form there is no other way to put it… it looks more less like a square:

The cursive version is a little easier. In the main form, if you add an extra “leg”, it almost looks like an “m”.

The final form is like a mirror image of a small handwritten “a”.

Nun

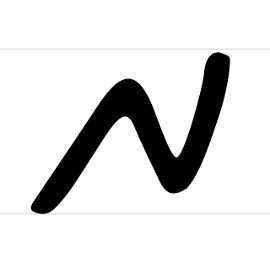

Nun () is a little boring to be honest.

As you might imagine the life of a nun would be.

The only excitement to be had is that it also has a final form.

A thin, long line.

Nothing e-nun-thusiastic to talk about really.

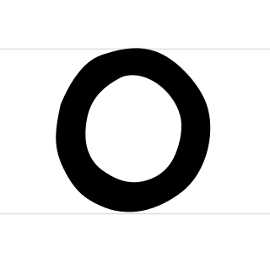

Samekh

This way of writing the sound “s” in Hebrew unfortunately looks just like an “o” ().

S.O.S you might want to say!

Thankfully it’s the same in cursive and print.

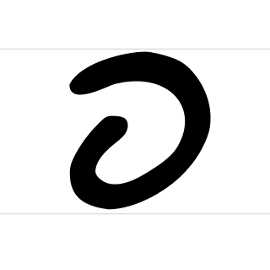

Ayin

Ayin () stands for one of the Hebrew sounds that is new to many Hebrew learners.

It’s a throat-originating muffled sound of… something almost like choking!

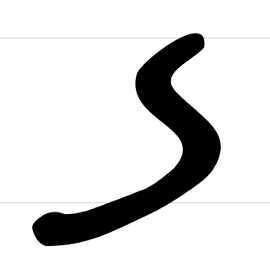

In cursive it looks like an upside-down ribbon, a symbol of support for various causes.

How to memorise it? Ay! in ribbons we trust!

The printed version looks like a flattened letter “y”. a-Y-in.

Pe

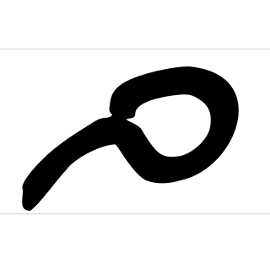

Pretzly-looking pe is delicious in both of its forms.

Look at it:

And no it’s not a mistake, print and cursive have a curl in different places — one curls on the bottom the other on top.

The final form of pe — because this is yet another letters that has a final form — is a little less organised.

Perhaps a beginner cook was trying to make a pretzel and didn’t entirely succeed… ()

Bear in mind pe can be read as “f”, depending on its position in the word and syllable.

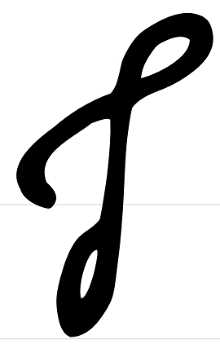

Tsadi

Tsadi sounds like a cicada — it goes tsk, tsk, tsk…

It’s also is a master of mirrors.

The printed letter is like a mirror image of a letter “y”, while the cursive is a mirror image of a capital cursive ”E”.

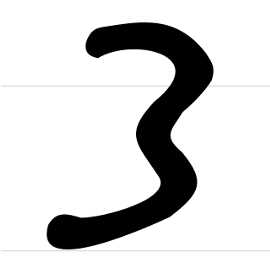

It also looks like the number three.

One two three… here comes tsadi:

To write the final form you’ll be calling up your best calligraphy and coordination skills.

While pe was an unfinished pretzel, final tsadi is a pretzel gone wild:

The final print form looks like a tuning fork.

Tune in for the cicada-like sound of tsadi.

Koph

When a squeezed resh sits on top of a final nun we get koph, a letter that stands for the same sound as kaph.

Ok, this is not the most simple of explanations… perhaps it’s easier to just see it:

Koph stands for the sound “k”.

Resh

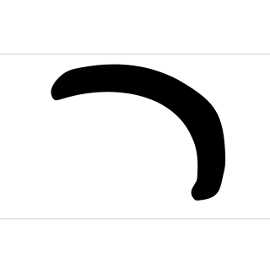

Resh looks like a rainbow.

Note of warning regarding print: be careful not to confuse it with dalet!

Rainbowy resh is a curve, while dalet has a clear right angle between the strokes. ()

Shin / Sin

Before we had some sounds that could be symbolised by the same character — like chet and kaph that both can stand for a sound “h”.

We also saw letters which are read differently depending on their position in the words, like pe or kaph.

Now we have one shape that can be read differently depending on nothing more than a gust of wind!

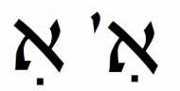

In theory shin and sin will be differentiated through a placement of a dot.

A dot in the upper right corner signifies shin — sound “sh”:

A dot in the upper left corner marks sin, sound “s” (yup, just like samekh):

So far so good.

However, these dots will often not be written either in cursive or in print.

The reader is expected to “simply know” what sound to read out — a matter of practice and familiarity with the words.

I still have a problem remembering where to place the dot for shin and where for sin (facepalm).

Here is what I learned though: there is usually no need to remember it (don’t tell anyone I said that).

Sin occurs much less often than shin.

If in an unvocalised text, you see the one odd dot marked on , there is a 99% chance it will be sin.

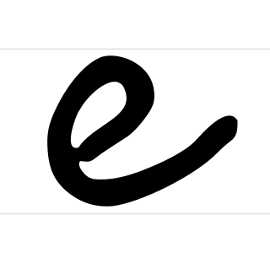

In cursive the letter looks like… a small handwritten “e”.

Tav

Tav () is not so tough! It looks like a resh with an extra leg.

The cursive version is nothing more than a lazy person writing the above.

But! You aren’t a lazy learner, are you?

What I suggest you do now is reread this post top to bottom with an aim to practice writing all the characters.

Am I right?

Vowels

Now you know all the consonants.

You might wonder though: where are the vowels?

As you know from my previous post, to mark the vowels Hebrew uses what’s called diacritics.

Diacritics (or diacritical marks) are pretty critical to reading, especially in the initial learning stages. These dots and dashes symbolise the vowels and tell you how to pronounce the words.

Apart from one or two exceptions they are placed under the consonants.

In the old days of grammatical complexity, vowels used to be pronounced differently depending on their length.

There are several different symbols to represent each vowel but — and it will be a relief for you to hear that – in Modern Hebrew the reading doesn’t differ!

The length of the vowels only matters if you’re learning to vocalise texts or are a student of Biblical Hebrew.

This will make our journey through the vowels much quicker.

We can simply divide them into groups, representing each sound.

A-class vowels that make the sound “ah”:

E-class vowels that make the sound “eh”:

I-class vowels that make the sound “ee”:

O-class vowels that make the sound “oh”:

U-class vowels that make the sound “oo”:

That’s it!

Modern Hebrew consonants and vowels.

You deserve a round of applause for getting this far.

But you’ll be mistaken if you think it’s the end of your journey, and I’m sure you know what the next step is.

Writing syllables.

Do you think you’re able to write your name now? Try it!

Grab the link to this article

Grab the link to this article